What I find interesting as fuck about this is that the car depicted is clearly a Jaguar XJ220.

Why, out of every car they could have chosen, did they decide on one of the rarest cars on Earth?

Because it’s in England, and the XJ220 is objectively the coolest car to come out of said country.

Apart from the McLaren F1.

My guess is this was made in 1992 or 1993

At that point the Jaguar XJ220 was the fastest production road car in the world.

It would have been a very short window in 92 before the McLaren F1 broke the record.

On 31 March 1998, the XP5 prototype with a modified rev limiter set the Guinness World Record for the world’s fastest production car, reaching 240.1 mph (386.4 km/h),[6] surpassing the modified Jaguar XJ220’s 218.3 mph (351 km/h) record from 1993.

So 1993 to 1998 for the independently verified record.

McLaren’s own test of the XP3 was in 1993 so it was really just waiting for that formality from that point on.

Yeah but that one’s not British.

The F1, made by British luxury automotive manufacturer McLaren, isn’t a British car?

Dunno what I was thinking, I think I saw the M and thought Mercedes.

What else were they going to use, the F1?

spear fishing target acquired. finalizing in-person first contact preparation.

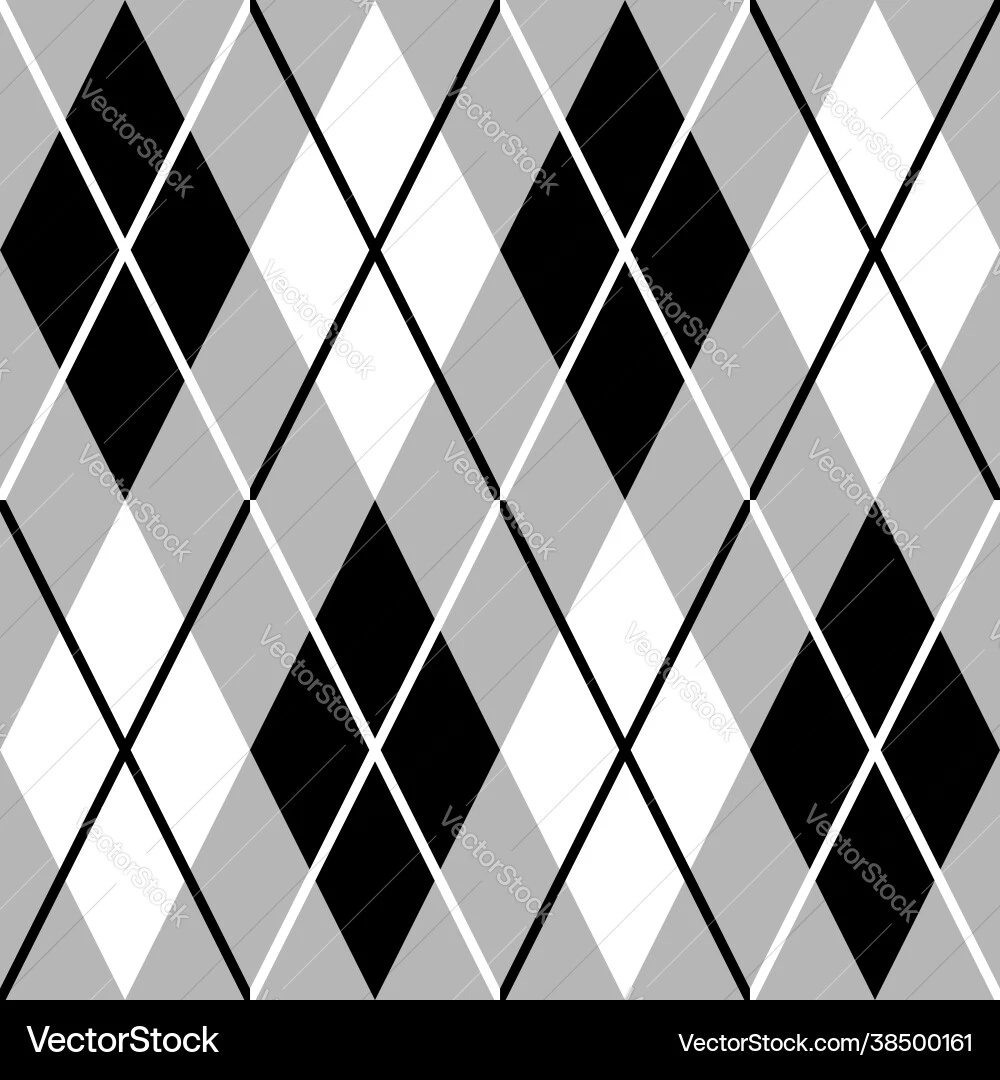

I’m willing to bet that this is no cross section of any road, but by “slice” they mean of things that were historically at that spot.

Nope, this is legitimately just pulled straight out of the ground when they were doing roadworks on it.

Any actual link that covers this? Or am I to just believe some random person on the Internet? Also, why would the ancient roads be built so far down?

When they were built, they were probably on top.

Understood. So are the current roads feet above the ground? If not, why are the others so far down?

I also assume this means you don’t actually have a link explaining this.

I don’t have a link for you or anything but just want to point out that it’s not just roads that are covered over time, otherwise archeology would be basically non-existent. For example, if ancient Roman stuff is commonly found in the UK ~5 ft or more under the ground, it makes sense that the roads would also be 5 ft under ground.

A lot of the roads that the Roman’s used are routes that are still in use today. If you’re going to pave a road from point A to point B, and there is already an old road there, might as well just build the new road right on top of the old one. You even out the sides of the road when building it, add some natural/artifical sedimentation over the next hundred years, and boom, the road and the whole area around the road is a few inches higher than it used to be.

This happens a few times over a few centuries and you end up with something that looks like the above. I’m not saying that that is an actual slice of a real road, but I don’t think that it necessarily means that it’s not possible.

I can’t find a source but I this is in the stone henge musuem. I’ve seen it in person and asked that exact question.

Also it’s pretty common for roads in places like the UK to just be built on top of each other like this.

It’s not specifically about roads per se, but I HIGHLY recommend Jacob Geller’s video “After a City is Buried”, which touches on how surprisingly common it is for us to just build new stuff directly on top of old stuff.

Never knew ancient squids used roads.

Well, they didn’t know it at the time

Oh please, the top isn’t that level.

Well they left off the road salt and that one leaf that got stuck on when they seal coated it last year.

True, but I was thinking there should be a pot hole in it!

Would these old roads really be stacked right on top of each other with no separation from earth and other build up?

Some places yes, keep in mind, some of these routes have been in constant use since the “track” era…

And especially the Roman roads have very well constructed foundations. So they were perfect for building right on top of.

often, yes.

Good question. Not in America, they usually just started from wagon tracks at best. I guess it depends on if they tore up the old roads first where they existed. Sometimes they used to integrate materials from the old road or nearby destroyed structures (after a disaster) as part of the new road, though not so much these days.

Sure, you could read Sarum (over 1k pages, onionleaf), or you just look at this picture and let the weight of history sink in

This is just the cross section of a road.

The rest of them are made of a kind of dark cheese, and riddled with holes.